TW: Detailed discussion about eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors

For some people, the meaning behind the term eating disorder feels distant and difficult to comprehend. For others, the term may bring up difficult feelings or feel deeply triggering.

Research estimates that as many as three in four people have disordered eating behaviors. In fact, health, nutrition, and fitness coaches, though well-intended, may be unknowingly promoting problematic eating behaviors.

For health, nutrition, and fitness coaches, learning about the signs and symptoms of eating disorders and identifying disordered eating behaviors are essential components of their knowledge toolbox. Learning about the disordered eating to eating disorder continuum not only helps coaches identify when a client may be exhibiting some of these behaviors but also helps to identify coaching practices that may be fueling disordered eating.

This article provides readers with an overview of the differences between eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors. It also introduces the reader to the continuum of disordered eating, which allows coaches to understand how some behaviors can initially seem harmless but may progress toward more unhealthy eating behaviors. Finally, it provides coaches with basic information on how to spot disordered eating and support clients in seeking the support they need.

Get Your Free Guide to Becoming a Holistic Nutritionist

Learn about the important role of holistic nutritionists, what it takes to be successful as one, and how to build a lucrative, impactful career in nutrition.

What Is an Eating Behavior?

When talking about individuals, an eating behavior is how and what a person tends to eat (or avoid eating) in addition to the thoughts and feelings associated with that way of eating.

An eating behavior is one element of overall health behaviors. Eating behaviors, like other health behaviors, result from a complex process of decisions, habits, mental state, social support, historical experiences with discrimination, access to healthcare, trauma, culture, economic access, and several others.

Some examples of eating behaviors include:

- When a person eats

- How often a person eats

- The interval between meals and snacks

- What motivates a person to eat certain things

- Eating more or less of certain foods

- Combining foods or not

- How a person feels about certain foods or components in foods

- What a person eats at different times of day and year

These are influenced by ideas, knowledge, tradition, and feelings associated with certain foods.

Before moving forward, it is important to acknowledge that the experience of eating for humans is a complex one. For humans, food is about nourishment as much as it is about the experience of eating. Other reasons that humans eat and why, other than for nourishment, are for pleasure, time availability, resource availability, and ideas about what they should eat and why.

Healthy and Problematic Eating Behaviors: Spotting the Difference

What Are Healthy Eating Behaviors?

A healthy eating behavior is one that helps to satisfy physiological needs (nutrients, water, energy) in addition to contributing positively to cultural, emotional, and social wellbeing. For example, a person with healthy eating behaviors can enjoy a chocolate chip cookie with a meal and feel good or neutral about honoring a craving without any repercussions on their self-image or planned activities for the day.

Below are some examples of healthy eating behaviors:

Healthy Eating Behaviors

- Eating a variety of foods

- Eating when you are hungry and stopping when you are full

- Knowing there are no “good” or “bad” foods

- Eating enough food to feel satisfied and meet the body’s needs

- Eating without undue guilt, anxiety, or other negative feelings

- Eating regularly most of the time (having a loose pattern of eating throughout the week)

- Eating treats, comfort foods, or fun foods occasionally without negatively affecting their self-image or emotions

Disordered Eating or Eating Disorder? Definitions and Facts

As a society, we tend to think about eating behaviors as two experiences on completely opposite, isolated poles; one pole is healthy eating behaviors, and on the other is unhealthy eating behaviors that include eating disorders.

This idea is flawed in multiple ways, of which we will mention a few. First, it assumes that there is an objective eating pattern that looks similar for everyone. In other words, it assumes that there is one “right” way to eat. Second, it doesn’t consider the progressive nature of behaviors toward and away from eating disorders. Third, it doesn’t consider that there are multiple diagnosable eating disorders in addition to disordered eating behaviors that often fly under the radar. And lastly, it overlooks the overlap between seemingly healthy food choices fueled by deeply unhealthy and unsustainable thoughts.

The Continuum of Disordered Eating

Today’s society is one in which rates of chronic diseases rise yearly. Many of those chronic diseases can be prevented, in part, by lifestyle, including diet. Widely available information about how lifestyle contributes to health and disease compounded by unrealistic societal standards of beauty and attractiveness has made way for a growing fear of food and fatness.

How does this affect eating behaviors? According to Temimah Zucker, Licensed Master Social Worker,

Societal standards and pressures, as well as preoccupations with weight loss and exercise, may lead individuals to alter/manipulate their food intake. For many people, this “works.” It does not interfere with their lives; they are able to find food they’re comfortable with at any restaurant, and there is no desire to change.

For others, this way of eating can be a precursor to a full-fledged eating disorder, and in many cases, it is hard to distinguish when an individual is struggling with disordered eating versus when an eating disorder is at play.

People can engage in disordered eating behaviors to a lesser degree or with less frequency than is generally considered diagnosable as a full-fledged eating disorder. This often happens because many disordered eating behaviors are normalized and even seen as healthy.

However, a person may progress from having disordered eating behaviors to developing an eating disorder if problematic behaviors are not identified early on.

As Dr. Russel-Mayhew states, “Diagnosable eating disorders are rare, but the behaviors that can lead to them are not.”

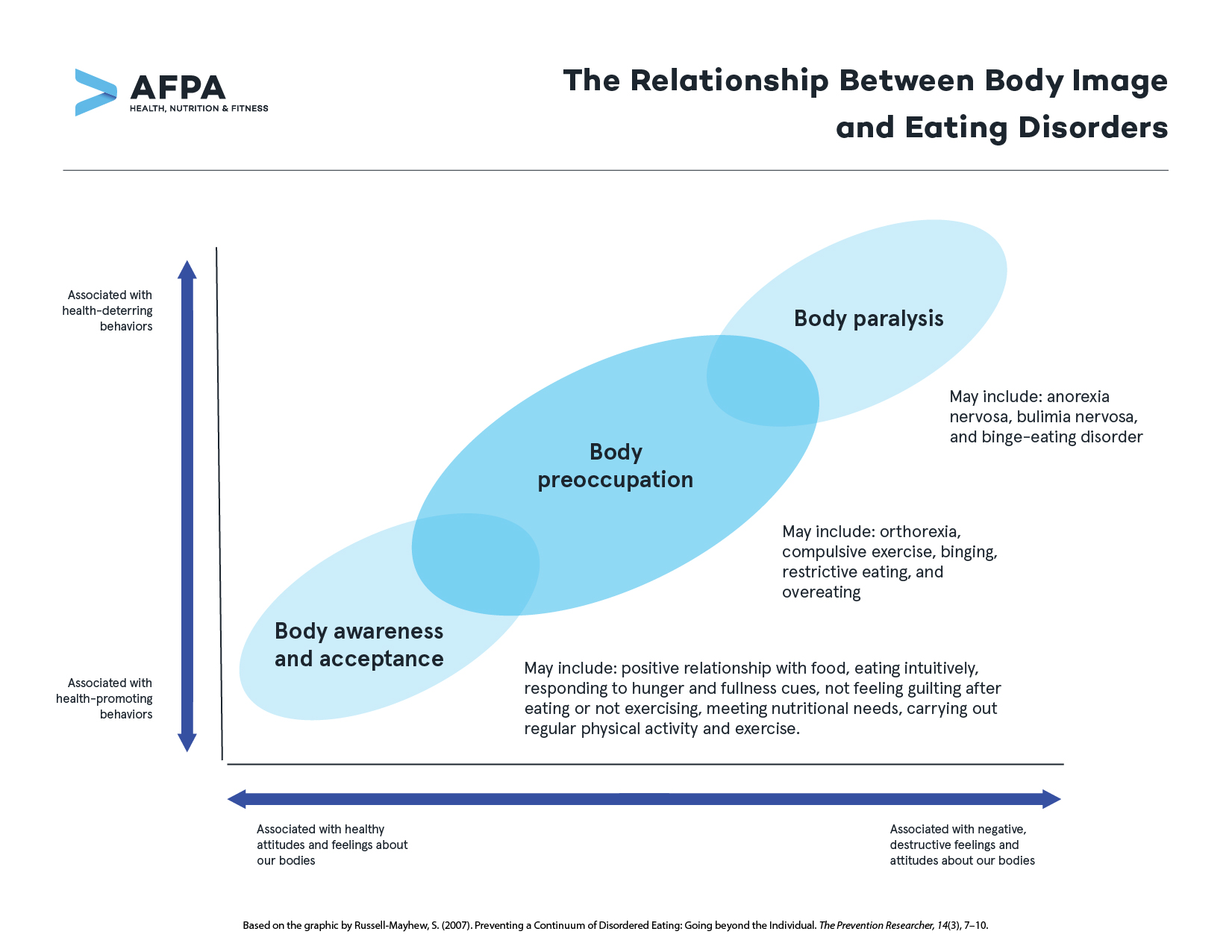

The BRIDGE Graph: Building the Relationship between Body Image and Disordered Eating

The graph below, based on psychologist Dr. Shelly Russel-Mayhew’s BRIDGE Graph, is a useful tool for visualizing the eating disorder continuum as it relates to body image. Each circle brings together individual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. The circles overlap, as they are not isolated but rather found on a continuum.

The first circle is body awareness and acceptance. It represents when an individual has an overall acceptance of the body and understands that appearance is only one element of who we are and self-worth is not dependent on appearance.

The second circle is body preoccupation, which is an over-concern for the body, particularly around weight and shape. A person may also be overly preoccupied with the internal functioning of the body, feeling that individual choices may have a significant impact on health status or disease risk.

The third circle is body paralysis, and this is associated with a feeling of immobilization or inability to control how we feel or take care of our bodies. The individual becomes fixated on controlling the body, and it takes more time and energy than anything else. Daily activities and quality of life are deeply affected.

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are psychological conditions that meet the criteria for diagnosis. There are four eating disorder diagnoses found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5): anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and eating disorder otherwise not specified. Additionally, orthorexia nervosa has been proposed as a fifth diagnosis, but more research must be conducted to refine the diagnostic criteria.

Types

The diagnosable types of eating disorders are as follows:

- Anorexia nervosa: “An eating disorder in which food intake is so severely limited that a person does not meet minimum weight requirements for height and age. People with anorexia nervosa fear fat, and the perception of their own body size is so distorted that it is difficult for them to recognize the seriousness of their condition.”

- Bulimia nervosa: “An eating disorder characterized by frequent binge eating episodes, followed by compensatory behaviors such as vomiting, over-exercising, or laxative and/or diuretic use. A person with bulimia is preoccupied with body shape and weight.”

- Binge eating disorder: Eating enormous amounts of food in short periods of time with no compensatory behaviors. Binges are associated with feelings of disgust, shame, and lack of control due in part to the frequency and intensity of the episodes.

- Other specified feeding and eating disorders: This is the most common eating disorder. “OSFED includes warning signs and related medical/psychological conditions that are similar to and sometimes just as severe as those of the other eating disorders.” Clinical examples of OSFED include atypical anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration, binge eating disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration, purging disorder, and night eating syndrome.

- Orthorexia: Not currently in the DSM-5 due to a lack of consistency for diagnosing criteria. A proposed definition of orthorexic behavior is “Persistent fixation on healthy nutrition and avoidance of food considered unhealthy in fear of developing an illness.”

Disordered Eating

Disordered eating is “when a number of unhealthy behaviors related to eating and exercise coincide. Examples of this include the use of steroids to increase muscle mass, tobacco use for weight loss or control, and occasional binging, purging, or fasting behaviors.” Disordered eating behaviors may be similar to some of the behaviors associated with eating disorders but are less frequent or of less severity. If they increase in severity, they may turn into a diagnosable eating disorder.

Disordered eating behaviors may also be called problematic eating behaviors. Problematic eating behaviors are those that cause physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, or social distress. For example, if a person is eating their mother’s traditional jerk chicken but feels guilty soon after because they think it is unhealthy, then it is not a healthy eating behavior. For a closer look at disordered eating behaviors and how to address them as a health coach, check out AFPA’s continuing education course Coaching Through Food & Body Image Struggles: Practical Strategies for Lasting Change.

Examples of Disordered or Problematic Eating Behaviors

- Recurring episodes of overeating

- Recurring episodes of undereating

- Modifying or desiring to modify eating patterns in response to recurring distress regarding body size

- Modifying or desiring to modify eating patterns in response to recurring distress about the healthfulness of an ingredient, food, or meal

- Fixating on molding the body into a certain body type or aesthetic through food, lack of food, or exercise

- Fixating on calories, food ingredients, and nutrients

- Depending on an external source to tell you to want to eat as a result of a recurrent distrust of your ability to make “the right” food choices

When someone has a problematic eating behavior, their self-worth is intrinsically linked to what they eat, what they don’t eat, how much they eat, and how often they eat, among others. Not adhering to their ideals leads to distress and a poor perception of self-worth.

Who Is at Risk of Developing Disordered Eating Behaviors?

Every sex, gender, race, ethnicity, age, and body type can develop an eating disorder and can adopt disordered eating behaviors. However, certain groups of people may be more at risk of developing disordered eating behaviors as a result of greater societal expectations related to their appearance and body type. In the West and regions influenced by Western beauty norms, those who may be most at risk of developing disordered eating behaviors include:

- People in larger bodies

- Men in thin bodies

- Athletes

- Models and influencers

That being said, everyone is under the influence of unrealistic beauty norms and the normalization of disordered eating behaviors. A survey carried out by the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and SELF Magazine found that:

- 75 percent of women reported disordered eating behaviors or symptoms consistent with eating disorders.

- 53 percent of women who diet are already at a healthy weight and are still trying to lose weight.

- 39 percent of women say concerns about what they eat or weigh interfere with their happiness.

- 27 percent would be “extremely upset” if they gained just five pounds.

- 13 percent smoke to lose weight.

There is a lack of similar data for men, often because eating disorders in men are underdiagnosed, under-treated, and misunderstood.

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) occurs when an athlete doesn’t consume enough fuel to meet the energy demands of their training and daily activities. This energy imbalance can lead to a range of health concerns, including decreased bone density, hormonal disruptions, and impaired performance. Over time, REDs can affect not just physical health but also mental well-being, increasing the risk of injury, fatigue, and burnout. Prioritizing proper nutrition and recovery is essential for athletes to maintain long-term health and peak performance.

What Does It Mean to Have a Good Relationship with Food?

When a person has a good relationship with food, they understand that food is for nourishment and for enjoyment and create space to honor both.

People with good relationships with food:

- Eat enough food in quantity and variety to meet their body’s nutrient needs.

- Don’t have strong feelings toward foods, ingredients, or food groups.

- Eat when they’re hungry, and don’t attempt to stave off hunger cues with water or gum.

- Do not do extreme diets.

- Know when they are full and generally respect the point of fullness. At the same time, they don’t feel guilty when eating past the point of fullness.

- Eat mindfully; they enjoy what they are eating, appreciate the qualities of the food and the socialization taking place around food.

- Accept their body as it is and feel grateful for what it is capable of doing.

- Are in-tune with the body’s cues after eating certain foods.

- Exercise primarily for long-term health.

How to Cultivate a Good Relationship with Food and a Positive Body Image

As a coach, you can help cultivate your clients’ positive relationships with food and their bodies by including a number of factors into your programs that will help to prevent eating disorder development. As you work through these, it is also important to be aware of potential biases of your own that may be inadvertently fueling disordered eating.

- Self-esteem: Appreciating body diversity and recognizing that outward appearance is only one element of who you are as a person.

- Critical thinking skills: Developing the ability to spot and critique advertising, marketing, and social media messages that reinforce unrealistic body ideals.

- Healthy eating: Discussing nutrient density, food group variety, energy needs, and hunger cues.

- Valuing meaningful foods: Talking about cultural foods, comfort foods, and celebratory foods.

- Physical activity: Learning about recommended levels of physical activity while also understanding the dangers of compulsive exercise.

- Respect: Respecting other people’s bodies and physical abilities. Discussing that bodies can be healthy at any size, shape, and weight. Recognizing that comments about other people’s bodies, even if they are meant to be a compliment, can trigger negative feelings and behaviors.

- Emotional health: Identifying feelings and learning coping and communication skills. Identifying how feelings are linked to eating behaviors and decoupling body appearance with negative feelings. Acknowledging and accepting that attempts to change the body will not resolve the negative feeling.

- Developmental changes and puberty: Understanding how developmental stages, body types, genetics, environment, and trauma can affect body development. For young people, this means preparing them for body changes, and for parents, it means encouraging positive body image and not shaming children for changes in their body.

- Problem-solving and decision-making skills: Identifying ways to counteract negative or contradictory messaging around body size and food. These may be promoted by family members, friends, culture, and society in general.

Get Your Free Guide to Becoming a Holistic Nutritionist

Learn about the important role of holistic nutritionists, what it takes to be successful as one, and how to build a lucrative, impactful career in nutrition.

Main Takeaways

Anyone can develop an eating disorder. Disordered eating behaviors are extremely common; as many as three in four people exhibit them. They often are not considered problematic or disordered because they are normalized or even considered healthy. Health coaches, without realizing it, may be promoting the adoption of problematic eating behaviors and poor self-esteem. Examining your own biases and being prepared to restructure your programs and messaging can help to build a space where your clients cultivate a healthy relationship with food and their bodies.

As a health, nutrition, or fitness coach, it is important to be aware of the signs of disordered eating, have resources for people who may benefit from support, and be prepared to make referrals when necessary.

References

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/contemporary-psychoanalysis-in-action/201402/disordered-eating-or-eating-disorder-what-s-the

- https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/blog/eating-disorders-versus-disordered-eating

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00555/full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3479631/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4303490/

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shelly-Russell-Mayhew/publication/234646541_Preventing_a_Continuum_of_Disordered_Eating_Going_beyond_the_Individual/links/00b7d53c5b1014746e000000/Preventing-a-Continuum-of-Disordered-Eating-Going-beyond-the-Individual.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Friederike-Barthels/publication/292398060_Orthorexic_Eating_Behaviour_A_new_Type_of_disordered_Eating/links/5bf7f133299bf1a0202db503/Orthorexic-Eating-Behaviour-A-new-Type-of-disordered-Eating.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shelly-Russell-Mayhew/publication/234646541_Preventing_a_Continuum_of_Disordered_Eating_Going_beyond_the_Individual/links/00b7d53c5b1014746e000000/Preventing-a-Continuum-of-Disordered-Eating-Going-beyond-the-Individual.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S000578940080012X

- https://www.cmaj.ca/content/165/5/547.short

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735815300386

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471015314001342

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471015313000548

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01190.x

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1469029211000306

- https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2050-2974-1-15

- https://barnard.edu/self-help-resources/continuum-of-eating